On the shores of the Indian Ocean, the Swahili Coast stands as one of the world’s most fascinating cultural crossroads. Stretching from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique, with islands like Zanzibar and towns such as Lamu at its heart, this region tells a story of centuries-long exchanges that shaped art, architecture, language, and identity.

The Swahili civilization emerged around the 8th century, when African communities along the coast began engaging in trade with merchants from Arabia, Persia, and later India and China. Over time, these interactions gave birth to a distinct culture — African at its roots, yet enriched by global influences. The Swahili language, a lyrical blend of Bantu structure and Arabic vocabulary, remains one of the most enduring legacies of this encounter and is spoken today by over 100 million people across East Africa.

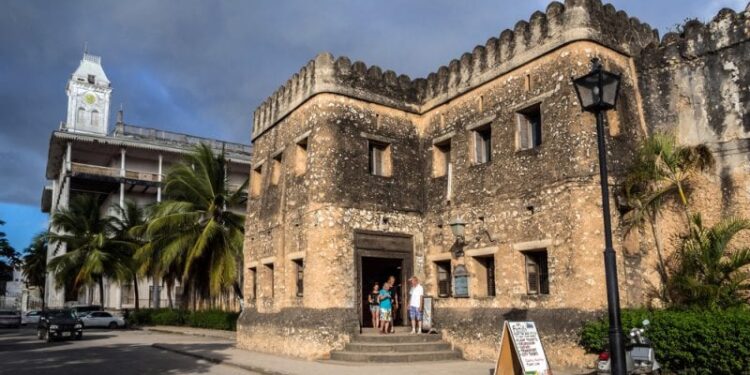

Zanzibar, once dubbed the “Spice Island,” became a global hub of trade in cloves, ivory, and slaves. Its Stone Town, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is a living museum of winding alleyways, ornate wooden doors, and coral-stone houses that reflect centuries of Omani, Indian, and European presence. Festivals like Sauti za Busara celebrate Zanzibar’s cultural dynamism, bringing together musicians from across Africa.

Lamu, Kenya’s oldest continually inhabited town, offers another glimpse into Swahili heritage. With its whitewashed mosques, narrow streets navigated by donkeys, and dhows anchored along the harbor, Lamu preserves traditions that have endured for nearly a millennium. Its annual cultural festival showcases Swahili poetry, dhow sailing competitions, and traditional craftwork, reaffirming the town’s role as a cultural anchor.

Beyond architecture and festivals, the Swahili Coast’s cuisine tells its own story. Coconut curries, biryani, pilau, and fresh seafood seasoned with cardamom and cloves reflect the blending of African ingredients with Asian and Middle Eastern flavors. Even today, food remains a powerful thread connecting generations and communities along the coast.

Yet, the heritage of the Swahili Coast faces challenges. Rapid urbanization, tourism pressures, and climate change threaten historic sites and traditional ways of life. Preservation efforts by local communities and international organizations aim to safeguard this legacy, ensuring that future generations can still walk the narrow alleys of Lamu or hear the call to prayer echo across Stone Town’s minarets.

The Swahili Coast is more than history — it is a living heritage, a testament to how cultures can merge, adapt, and thrive across centuries. Zanzibar, Lamu, and the wider coastal strip remind us that identity is never static but shaped by encounters, resilience, and creativity.